Roman Kamushken

Intro: The myth we were sold

We all got into UX because we believed in something.

Maybe it was the thrill of solving real user problems, the beauty of good design, or the dream of making things easier, clearer, and more human. We wanted to create elegant solutions. We wanted to be useful.

But somewhere along the way, we realized something else: the hard part isn’t the pixels. It’s not the wireframes or flows or accessibility audits. Those are the parts we can do in our sleep. The hard part is getting any of that work to actually ship.

It’s navigating a mess of politics, priorities, power struggles, egos, fiefdoms, and the quiet but constant resistance to change. And no one warned us. No one told us that the real UX job begins after the design is done.

Chapter 1: The hidden job nobody told you about

In school, or bootcamp, or wherever you came from, the job was framed like this:

❶ research the problem, ❷ understand the user, ❸ prototype a solution, ❹ test it, ❺ refine it, ❻ hand it off. Easy game!

But in real life your handoff gets ignored. Your research gets questioned and your solution gets watered down. The PM ghosted, due the dev team has other priorities. Leadership changes direction halfway through the sprint. And now your elegant, thoughtful design is a dead file in a dusty Figma project.

The real job is not just to design. It’s to persuade, align, evangelize, communicate, and adapt; often pitching the same idea ten different ways to ten different people, hoping one of them gets it. It’s relentless.

As one UX veteran on Reddit put it: "The longer I’m in this field, the more I realize the hard part about UX isn’t just about designing great products or features. It’s about actually getting them into production."

And that’s the truth. We’re not just designers:we’re diplomats, translators, strategists, therapists, and sometimes, even punching bags.

Chapter 2: Welcome to office politics, you now live here

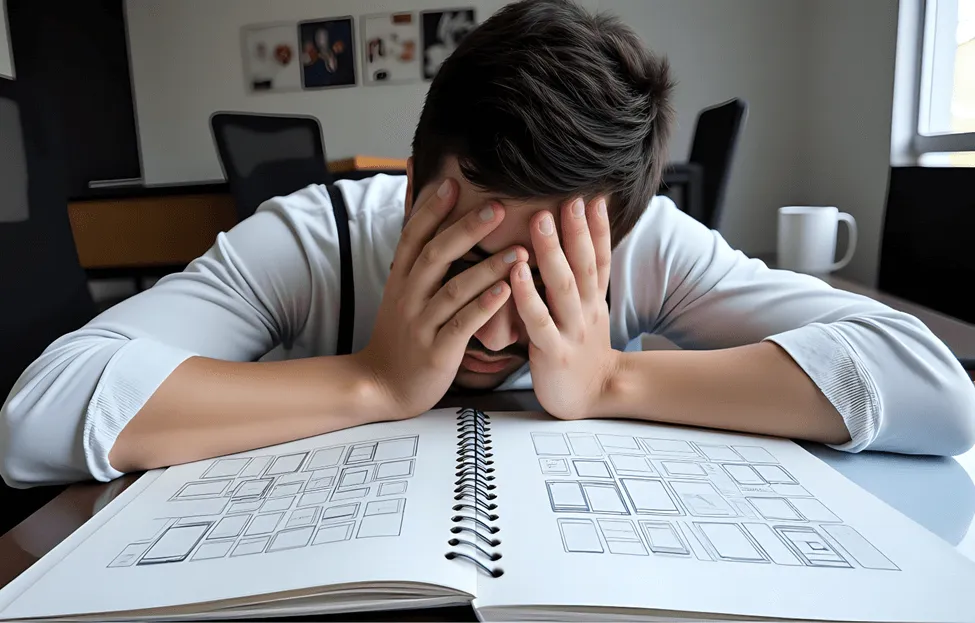

No one tells you how much of UX is emotional labor.

You’re managing your team’s insecurities, a PM’s vision, an engineer’s technical constraints, and a director’s KPIs - all while trying to advocate for the actual user.

My fellow designer shared, "Dealing with office politics took more time and drained more of my energy than the most complex design task I ever undertook." That hits because it’s true.

UX becomes a game of optics.

Who supports your work? Who opposes it, quietly or openly? Who can veto it at the last moment? Who needs to feel like it was their idea? Who do you need to pre-align with so your review meeting isn’t a bloodbath?

You start having "pre-meetings" before the actual meetings. You review slide decks before review decks. You walk on eggshells. Not because your design is bad, but because someone in the room might feel threatened by your suggestion.

This is what no bootcamp prepares you for: the slow erosion of clarity by committee. The art of protecting the core of your idea while navigating through sludge.

Chapter 3: When a button takes 18 months

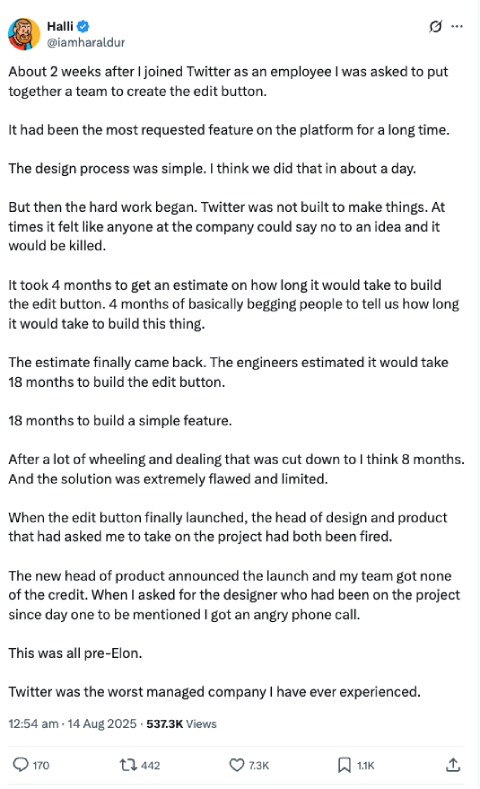

"Just add an edit button."

That’s what started it all. A former Twitter employee shared how a simple feature spiraled into months of work, pushback, and internal chaos. On the surface, it was a button. In practice, it challenged the foundation of the product.

One of the most upvoted replies was a blunt reminder: "If a ‘simple’ feature is obviously broken or missing, there’s a reason for that. The tech stack or management processes are too dysfunctional to have sorted it sooner."

This is a truth that hurts. Designers often get blamed for inaction or slowness.

But behind every dead-on-arrival feature lies a tangled web of legacy systems, disjointed teams, bad assumptions, and "not my job" mentalities.

Even small changes can take months when no one owns the full stack. Or worse: everyone thinks someone else does.

Chapter 4: You are not an artist and that’s OK

There comes a moment in every UX career when you realize: you’re not here to make pretty things.

You’re not paid to be creative; you’re paid to be effective.

And that hurts, especially if you came from a design background. It feels like you sold out. It feels like you lost the thing that brought you here.

But what if you didn’t lose it? What if this is the next level?

One comment in the thread, I mentioned above, nailed it: "They’re not paying us to do arts and crafts. Businesses hire employees because they expect that employee to make them more money than it costs to hire them."

This doesn’t mean abandoning craft. It means understanding how to weaponize it.

You still care about type scales and contrast ratios. But you also care about adoption rates, support tickets, drop-off points, retention. You start caring about problems that your users don’t even know they have yet.

You mature.

Chapter 5: When you thought it was just about good UX

A lot of us feel betrayed. We thought we were signing up for user advocacy, clean interfaces, and thoughtful flows. Instead, we found ourselves locked in rooms with people who don’t understand UX and don’t want to.

One senior designer said: "Those who survive are those who excel at delivering business value, not necessarily those who excel at the design process."

That stings. Because it forces us to ask: are we in the wrong field? Or are we just playing the game on hard mode?

Maybe we were naive. But maybe that idealism is still useful. Maybe the frustration we feel is the tension between what UX could be, and what we’re allowed to make it.

And maybe that tension is where the real work lives.

Chapter 6: What should you do with all this information

If you've made it this far, chances are you’ve seen some version of this chaos in your own UX work. Perhaps, you’ve lived through the invisible battles, felt the weight of unspoken politics, or quietly questioned if this job is still about designing for users at all.

So now the question becomes: what do you do with all of this?

You don’t need a career pivot or a new title. You need a clearer lens.

Start here:

- Stop internalizing the mess.

The dysfunction around you is not a reflection of your skill. Most of what wears UX people down isn’t in the craft, it’s in the friction between craft and context. Recognize that, and you stop feeling like you’re bad at your job. - Shift your definition of “good UX”.

It’s not just beautiful flows or clever interactions. Good UX might look like: saying something hard in a meeting, rerouting a bad idea before it becomes a feature, or earning enough trust that people actually listen when you talk about users. - Pick your battles. Then document the wins.

Don’t try to fix everything. Fix what you can reach. And when something works - capture it. Build a quiet proof-of-trust portfolio. Not for Dribbble. For yourself. - Reframe your influence.

You’re not “just” a designer. You’re a translator, a connector, a negotiator, sometimes a therapist. The sooner you own those roles, the sooner they become strategic, not invisible. - Protect your energy.

Seriously. If this chapter hit too close to home, it means you care. But caring doesn’t mean carrying everything. Step back when you need to. Rest. You’re not a bottleneck. Treat yourself like one.

You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to stay aware, stay adaptive, and stay human.

That’s the real job now.

Outro: You were never just a designer

If you’ve ever walked out of a meeting feeling like your soul got stepped on, this post is for you.

If you’ve ever spent weeks getting everyone aligned just to ship a feature no user even notices, it's for you.

If you’ve ever wondered if you’re burned out or just fed up with bullshit... Is for you.

Because this is the job. It’s messy. It’s political. It’s draining.

But it’s also important. And it’s yours.

You weren’t wrong to believe in good design, to want to make things better, or to care deeply about the outcome.

But now you know: caring isn’t enough. Designing isn’t enough.

Shipping is the hard part.

And navigating bullshit (quietly, strategically, persistently) is the real UX.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)